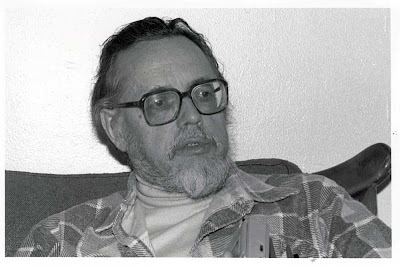

I recently noted this article about JHY in the New York Times. When I was in school, Yoder was on campus at Goshen College because the seminary was still in Goshen. I remember him as usually looking disheveled and seemingly in another world. As the article notes, his scholarship is both embraced and criticized, and continues to be analyzed long after his death, but his behavioral misdeeds make understanding his work and the church's response even more complex. The article

link is here.

A Theologian’s Influence, and Stained Past, Live On

By

MARK OPPENHEIMER

Can a bad person be a good theologian?

All of us fall short of our ideals, of course. But there is a

common-sense expectation that religious professionals should try to

behave as they counsel others to behave. They may not be perfect, but

they should not be louts or jerks.

By that standard, few have failed as egregiously as John Howard Yoder,

America’s most influential pacifist theologian. In his teaching at Notre

Dame and elsewhere, and in books like

“The Politics of Jesus,”

published in 1972, Mr. Yoder, a Mennonite Christian, helped thousands

formulate their opposition to violence. Yet, as he admitted before his

death in 1997, he groped many women or pressured them to have physical

contact, although never sexual intercourse.

Mr. Yoder’s scholarly pre-eminence keeps growing, and with it the

ambivalence that Mennonites and other Christians feel toward him. In

August, Ervin Stutzman, executive director of

Mennonite Church USA, which has about 100,000 members, announced the

formation of a “discernment group” to guide a process to “contribute to healing for victims” of Mr. Yoder’s abuse.

In 1992, after eight women pressured the church to take action, Mr. Yoder’s

ministerial credentials were suspended

and he was ordered into church-supervised rehabilitation. It soon

emerged that Mr. Yoder’s 1984 departure from what is now called

Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary,

in Elkhart, Ind., had also been precipitated by allegations against

him. He left for Notre Dame, where administrators were not told what had

happened at his last job.

But Mr. Yoder emerged as a hero of repentance. His accusers never spoke

publicly, and their anonymity made it easier for some to wish away their

allegations. And in December 1997, after about 30 meetings for

supervision and counseling, Mr. Yoder and his wife were welcomed back to

worship at Prairie Street Mennonite Church in Elkhart. To cap a perfect

narrative of redemption, he died at 70 at the end of that month

.

Without denying the wrongness of his acts, his supporters continued to

celebrate Mr. Yoder and the Mennonite leaders who had rehabilitated him.

“How John’s community responded to his inappropriate relations with

women” was “a testimony to a community that has learned over time that

the work of peace is slow, painful, and hard,” wrote

Stanley Hauerwas, a retired Duke University professor and Yoder’s heir as the leading pacifist theologian, in his

2010 memoir.

Mr. Yoder’s obituary in The New York Times did

not mention his sexual misdeeds. None of his victims received monetary

settlements. Mr. Yoder apologized, sort of, with a statement that “he

was sorry that we had misunderstood his intentions, as he never meant to

hurt us,” according to Carolyn Holderread Heggen, one of the eight

complainants.

Ted Koontz,

a professor at Mr. Yoder’s old seminary and a member of the church’s

discernment group, said the church needed to take stock of what was — or

was not — done for Mr. Yoder’s victims.

“There are a lot of different opinions about what was done and wasn’t

done to hold him accountable,” Professor Koontz said.

The committee will probably conclude its work, he added, in time for the

Mennonite Church USA’s 2015 convention in Kansas City, Mo., where there

may be a ceremony “of confession, repentance, reconciliation.”

Of course, reconciliation was what the four-year process in the 1990s

was supposed to achieve. It obviously failed. And Mr. Yoder remains

inescapable for Mennonites, his work read and referenced often and

everywhere.

“Physically he died, but his work and his theological writings live on,”

said Linda Gehman Peachey, a freelance writer in Lancaster, Pa., who is

also part of the six-member group. “For those who have known this other

side — his behavior, particularly toward women — that is really

painful.”

Mr. Yoder’s memory also presents a theological quandary. Mennonites tend

to consider behavior more important than belief. For them, to study a

man’s writings while ignoring his life is especially un-Mennonite.

Professor Koontz regularly tells his students reading Mr. Yoder that

“his behavior is one thing we ought to take into account when we read

his work.” Ms. Peachey noted that Mr. Yoder wrote a good deal about

suffering as a Christian virtue, but “if you know this part of the

story” — how he made women suffer — “you tend to read it with a

different eye.”

Mr. Yoder seemed very attentive to the notion that theology should align

with behavior. It turns out that in unpublished papers, he formulated a

bizarre justification of extramarital sexual contact.

In his memoir, Professor Hauerwas alludes to what Tom Price, a reporter for the newspaper The Elkhart Truth, described in a

five-part 1992 series

as Mr. Yoder’s defense of “nongenital affective relationships.” Mr.

Yoder said that touching a woman could be an act of “familial” love, in

which a man helped to heal a traumatized “sister.”

Mr. Price quoted from “What Is Adultery of the Heart?” a 1975 essay in

which Mr. Yoder wrote that a “bodily” embrace “can celebrate and

reinforce familial security,” rather than “provoking guilt-producing

erotic reactions.”

Ms. Heggen, called Tina in the newspaper articles, told Mr. Price that

Mr. Yoder had a grandiose explanation for his advances, which he tried

out on multiple women.

“We are on the cutting edge,” Mr. Yoder would say, according to Ms.

Heggen. “We are developing new models for the church. We are part of

this grand, noble experiment. The Christian church will be indebted to

us for years to come.”

On Wednesday, Ms. Heggen, agreeing to be identified as a victim for the

first time, recalled driving Mr. Yoder to the Albuquerque airport in

1982. He asked her to get out for “a proper goodbye,” Ms. Heggen said.

“Then he pulled me into his belly and held me tight for a painfully long

time. I realized I couldn’t escape his clutch.”

In 1992, Ms. Heggen, who now lives in Oregon, published

a book about sexual abuse.

Traveling the world, lecturing about her book, she said she met

“significantly” more than 50 women who said that Mr. Yoder had touched

them or made advances.

“Women inevitably come up after these events and tell you their story,”

Ms. Heggen said. “The scenario was so familiar to me, and I would

interrupt them and say, ‘Are you talking about John Howard Yoder?’ They

would say, ‘How did you know?’ ”

After his advance toward her, Mr. Yoder mailed Ms. Heggen an essay in

which he advocated physical contact, including nudity, between unmarried

people, so long as “there wasn’t lust.”

Ms. Heggen had a theory of what Mr. Yoder might have been thinking. “ ‘I

have created this great peace theology,’ ” she began, trying to put his

thoughts into words. “ ‘And you and I are developing a new Christian

theology of sexuality.’ ”