For a long time, I have been aware of the Mennonites who migrated to Mexico to live and farm in The Chaco and elsewhere. A

nice summary is here. Locations shown below.

Mennonite/Anabaptists have a long history of migration, generally to avoid conflict and religious persecution, but also to find new land for farming and family living. The

New York Times recently had a lengthy article about the Mennonites in Mexico, and of the conflicts there, and once again, looking to move on after many decades in Mexico.

Read the article given in the link, most of which is copied below:

RIVA

PALACIO, Mexico — On the edge of a high plain fringed by craggy

sandstone hills, Johan Friesen’s small farm is a testament to the rural

providence of his Mennonite people.

Neat

fields of onion, soybean and yellow corn stretch behind his concrete

and adobe house. In the farmyard, a few dozen cows stand in a corral,

ready for milking, and a canary-colored reaper awaits repair. But

beneath this valley of orderly farms in the center of Chihuahua State,

the picture is less than serene, officials and farmers say.

Underground

reservoirs have been drained by thirsty crops, like corn, that are the

mainstay of the Mennonites’ success, they say. Competition for

groundwater — which officials have warned could run out in 20 years —

has strained relations between the pacifist,

Low German-speaking Mennonites and other farmers and, on occasion, incited violence.

In

Chihuahua, nearly a century after the Anabaptist Mennonites migrated

from Canada and transformed this valley into a lush carpet of crops,

hundreds are trading the land they call home for one where land is

cheaper and water is more plentiful.

“People

say the water is going to run out,” said Mr. Friesen, 44, who in the

spring will join 25 Mennonite families who have begun a new colony in

central

Argentina. “Without water you can’t grow anything.”

Santa

Rita, in Mexico’s Mennonite heartland, is a colony of one-story,

pitched-roofed homes, clipped lawns and straight roads — a world away

from a typical Mexican village.

On

a recent Saturday, perhaps the loudest noise was that of a lawn mower,

steered by a young woman wearing a long dress and a straw hat.

For all their good husbandry, though, Mennonite farmers have been prodigal consumers of groundwater, experts said.

“Water

has been a source of wealth in Chihuahua, and while that wealth lasts,

people are not thinking about how much they are using,” said Arturo

Puente González, an agricultural economist.

Still,

it was “very unfair” to blame the region’s water problems on the

Mennonites, said Kamel Athié Flores, the head of the Chihuahua branch of

the National Water Commission, known as Conagua, which regulates

supply. He pointed to city dwellers and big non-Mennonite farms that

produce apples and pecans — also thirsty crops.

Cornelius

Banman, a farmer from the Manitoba colony, about 50 miles south of

Santa Rita, said nobody complained about the pecan farmers because they

were of Mexican descent and, unlike Mennonites, who do not vote, had

political clout.

“They look on us as foreigners,” he said.

The

Mennonites live apart in their colonies and rarely marry outside,

though they pay workers above-average wages. The most conservative

eschew electricity and other devices that would link them to the outside

world.

Others

use WhatsApp, a messaging application, and research land prices on the

Internet, but they discourage distractions like Facebook.

The

women speak little Spanish, and children are raised for a “wholesome”

rural life, attending Mennonite schools until eighth grade.

The

Mennonites began digging wells for irrigation in the 1980s, said Víctor

Quintana Silveyra, a sociologist and politician in Chihuahua City who

has studied local water use. As their population grew — they estimate

their number at 60,000 — they used credit from

Mennonite banks to buy land in the desert and to install irrigation

systems. Since 2000, irrigated land in Chihuahua has doubled, to about

1.3 million acres, and farmers are pumping water at an “exploitative”

rate, Mr. Quintana said.

Farmers

said wells had to be dug three times deeper today than they were 20

years ago, a process some cannot afford. To slow extraction, the

government in 2013 ruled that all new wells require a permit.

“I

can see a point, in my lifetime, when the water here is finished,” said

Luís Armando Portillo, a farmer who is the president of the Technical

Committee of Groundwater in Ciudad Cuauhtémoc.

A

group of activists known as El Barzón has campaigned to shut down

illegal wells and break dams on Mennonite land. Joaquín Solorio, a

Barzón activist whose parents had to sell their cattle after their well,

next to a Mennonite farm, dried up, said the group had lodged

complaints about illegal water use. “It’s not just Mennonites,” he said.

Defending

water rights can be deadly in Chihuahua, where links between organized

crime, mining and farming are murky. Alberto Almeida Fernández, a former

politician who protested against illegal wells and against a Canadian

mining project, died after he was shot in February. Two other activists,

Mr. Solorio’s brother and sister-in-law, were killed in 2012. The

police have yet to solve the crimes, and members of Barzón — three of

whom have state police escorts — discard a Mennonite connection. But the

deaths have added to tensions.

“You

think about buying land, and then you think, ‘I don’t want problems,’ ”

said Johan Rempel, a leader of the Manitoba colony who is looking for

land overseas for about 100 families.

In

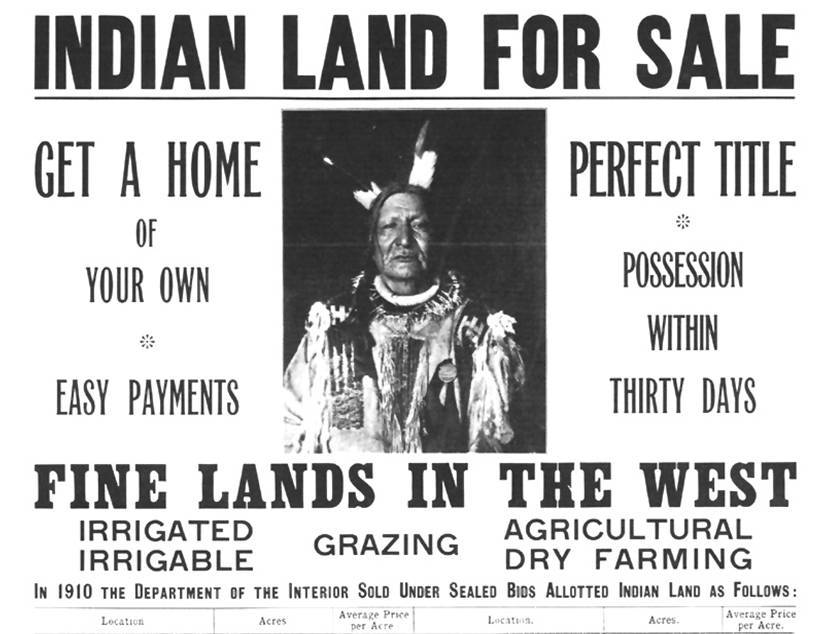

some ways, the Mennonites’ migration is another turn of history. Those

who moved to Mexico from Canada had fled persecution in Russia. Over the

years, some settled in other parts of Mexico, and conservative groups

broke from the Mexican colonies and moved to Bolivia, Paraguay and

Belize.

But with younger farmers facing

new pressures

— difficulty getting permits for wells, and soaring costs for irrigated

land — some predict that they will look to find land elsewhere.

About

50 of the 300 families in Mr. Friesen’s colony, Santa Rita, will move

to San Luis Province in Argentina, said Abraham Wiebe Klassen, the head

of the colony. Other colonies have looked at land in Russia and

Colombia.

The perception that Mennonites are more attached to their culture than to their country irks other farmers.

“Their world is everywhere,” Mr. Portillo said. “They arrive, they work the earth and when they need more, they move on.”

“This is my land,” he added. “My dead lie here. I won’t leave.”

Abraham

Wiebe Wiebe, who was preparing to leave for Argentina with his wife and

children, disagreed. “I’m 100 percent Mexican,” he said.

Sitting

in his kitchen as his wife rolled out cookies, Mr. Wiebe, 49, said he

had “lost a lot of sleep” over leaving. “But our children have no future

here,” he said.

Several

Mennonite farmers said they were skeptical that Chihuahua would run

dry. Water was God-given, one farmer said, and only God could take it

away.

“Doesn’t water go in a cycle?” Mr. Wiebe asked. “You pull it from the ground, and then it rains from the sky.”

Others

are less sanguine. Nicolas Wall, a Mennonite who farms 700 acres of

corn with his brother, worries that there will not be enough water for

his children to farm.

“I think there’ll be an end to it sometime,” Mr. Wall said. “But when?”

The

real problem lies with the government, farmers and experts said. The

water commission is a “den of corruption,” Mr. Klassen said, a place

where officials take years to process paperwork and sell well permits

for thousands of dollars.

Mr. Athié did not deny corruption, but said the problem was “older than Christ.”

Mr.

Puente said Mexico needed to start a national conversation. People are

turning to other energy sources, he said, adding: “But there is no

alternative to water. Water is water.”

Mr.

Friesen will trade such worries for the challenge of starting a new

life on the 250 acres he bought in Argentina. Those already there have

built some houses and bought cattle, he said. Three babies have been

born.

Hard

as it would be to leave “the homeland,” Mr. Friesen said, his five

children would “put down roots” in a new place. Standing in the dairy

barn as his wife, Gertruda, milked cows, he smiled.

“We’re going to create exactly the same world there that we built here,” he said.