Each year when Veterans Day rolls around, I always have to think a bit about what makes a veteran a veteran and what is a person who did two years of service, but not in the military. By definition, the veteran of Veterans Day is specifically referring to persons who have served in the U.S. armed forces. So, I am not a veteran although from 1968-1970, I did two years of alternative service as a conscientious objector. This was during the height of the Vietnam war, although the Vietnamese call it the American war. Close to Veterans Day in 2007, I visited Vietnam and wrote about it here. At that time, my very good friend and college classmate Clair Miller, who had served in Vietnam, said "Well, you finally made it!" This year marks the fortieth year since I completed my alternative service commitment, and I dug out my copy of Stories of Peace and Service, a compilation of brief stories of members of Beth El Mennonite Church in Colorado Springs who had chosen not to participate in the US armed forces. The 1990 book was edited by Stan Hill, who was also a conscientious objector during the Vietnam conflict. Here is what I wrote twenty years ago, and it still rings quite true today.

"Looking back, I believe that a subtle tension has always been present in my family. It is never too obvious, especially to the young, but there definitely is a difference between the uncles and cousins that have served in the armed forces and those who have not. With fifteen uncles and innumerable cousins (seemingly), there is a variety of service backgrounds ranging from wartime veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam, to peacetime veterans, to service exemptions for farm, age, physical, and student status, to cousins never faced with conscription, to me - the only one of the entire group that registered as a conscientious objector and was drafted into alternative service.

I grew up attending the Goshen College (IN) Mennonite Church. It was the church, and specifically assistant pastor Bob Detweiler, that guided me and several others who were soon to turn 18, to register for the draft as conscientious objectors. I don't have any specific recollections of discussions with my parents about registering as a CO. I think that they assumed that I would register as a conscientious objector and do I-W service. I attended numerous indoctrinational meetings at the church. We learned what questions were going to be asked on the CO application form and what we might expect if we were called before the draft board.

It was early in 1963, I was 17, and the whole registration process didn't have much meaning. I knew that after high school, I would be going to college. College meant an automatic student exemption from the draft, so I really didn't give much serious thought to the consequences of being drafted. Also, New Paris was not exactly a hotbed of national and international awareness. Kennedy had recently been assassinated, and Johnson quietly assumed the presidency while a nation chronicled the death of a President. We witnessed an orderly transition of power that could not take place in many other nations. Camelot was replaced by the Great Society. No discussions centered on our "advisers" in Southeast Asia.

I was a little nervous when I filled out the lengthy CO questionnaire. I had thought about what I was going to write, but it was more like taking an exam that a testament of commitment. Since I turned 18 in May of 1964 and had already been accepted for enrollment at Goshen College, my draft status automatically became I-S (student deferred).

Interestingly, my draft card was signed by one of my uncles, Paul T. (Red) Emmert, of New Paris. Red was a Navy veteran of WWII and had married one of my mother's younger sisters. Red was involved in Jackson Township politics, and an appointment to the draft board was a county-level political prize. There probably aren't too many people that registered as CO's that had an uncle on their draft board!

Four years at Goshen College increased my international and political awareness by several orders of magnitude. Vietnam had transformed from a conflict into a war. A few advisers had been replace by tens of thousands of U.S. combat troops. The war escalated; conscription escalated; debate escalated; protest escalated; and resistance escalated - and the draft became a reality.

Before I had to face the draft in the spring of 1968, two good friends of mine were drafted. One friend, Clair Miller, had dropped out of college and was waiting for his draft notice. We talked about what he planned to do since in 1967, being drafted was nearly equivalent to going to Vietnam. The four options of the day were (1) go; (2) go, but request assignment as a non-combatant; (3) head for Canada; or (4) request CO status. The glitch in the latter was that because there was a war going on, receiving CO status was difficult unless you had initially registered at 18 as a conscientious objector. Clair, being a rather rebellious type, decided that he would go into the army and let the chips fall where they may.

My second friend and college roommate, Marlin Nofziger, graduated after the first semester of our senior year with a degree in biology. He had requested and received CO status from his draft board in Ohio. Then he found an acceptable alternative service assignment working as a technician in the pathology research laboratory of Dr. G. Barry Pierce at the University of Michigan.

The 1968 draft was based on the lottery. The 366 possible days of the year were drawn at random, and eligible individuals were drafted by birth date. A sizable group of college guys sat around the TV watching the outcome, knowing that a number in the range of 150 or so would surely be drafted, and anything beyond 200 had a chance of not being drafted. Most of them were committed to doing I-W service in the event they were drafted. May 3 came up in the first 50 numbers. Therefore, I knew that as soon as I graduated and no longer had a student deferment, I would be drafted - and I was.

Being drafted meant a trip to Chicago for the infamous physical - an all day affair that should have taken about an hour. Hurry up and wait. Eye check. Ear check. Leg check. Heart check. A friend from high school, Dick Kerlin, was in our group. When we got to the cardiologist, he handed the doctor a note about his heart murmur. The doctor just stuck it in his pocket and proceeded to listen to Dick's heart. As the doctor listened, Dick said "I have a murmur," to which the doctor replied, "What?" this exchange occurred two more times, and Dick gave up. Not too many people flunked the physical.

Without ever being called before the draft board, I received a I-O classification. I was told to find an acceptable assignment for my two years of alternative service. I contacted Marlin at Michigan, and he told me that they were looking for more technicians because the entire Pierce laboratory was going to be moving to the University of Colorado Medical Center in Denver. I went to Ann Arbor for an interview, was hired, and made arrangements to begin my assignment in Denver in late August of 1968. Since I had a bachelor's degree in science, I was lucky to get a job somewhat related to my college background. Other graduates in my class from Goshen were assigned as operating room coordinators, orderlies, and other jobs.

Marlin and I and another GC graduate, John Bender, shared an apartment close to the medical center. We worked in three different laboratories, but pretty much had hassle-free jobs. Our lab directors all knew that we were COs and generally sympathized with our decision since none of them were particularly keen on the U.S. involvement in Southesast Asia. They also appreciated our willingness to occasionally come in to work on evenings and weekends. Of course, what were we going to do - complain to our draft boards that we were overworked!?

Throughout 1968 and 1969, Clair and I exchanged letters, keeping in touch as he made his way through basic training on the way to becoming a PFC grunt assigned to 365 days in South Vietnam. He came to Denver right before he was sent to Vietnam. Clair was always good at covering his feelings with an easy-going facade, and this visit was no different. However, we both knew that he came to Colorado because it could have easily been the last time we could get together. Clair left for 'Nam, and my life went on with a minimum of disruption. In 1968, Rhonda and I decided to get married, and during the middle of my two years of I-W, on June 15, 1969, we did.

The letters back and forth from Vietnam continued. There was some regularity, but often there would be a gap. Then another letter would arrive. Clair never gave too many details, but I could tell it was tough - 12 hour firefights, loss of another armored vehicle driver, pinned by the VC for four days, risking further casualties to retrieve an friend's body because you knew the he would have done it for you, sitting in your dugout counting the clicks of incomings knowing that they're getting closer. I prayed a lot for Clair. Clair made it out of Vietnam without ever being hit, one of only three in his entire company to make it unscathed (physically) through the entire 365 days.

I have seen Clair several times since those days. I was his best man at his wedding; he and his family visited us in Colorado on a skiing vacation, and so on. We write and phone occasionally. We seldom discuss the Vietnam era, but when we do, it's usually just the two of us.

I have read Rudy Wiebe's Peace Shall Destroy Many and, even today, I still am puzzled by the paradox of being a conscientious objector in the United States. I believe that nonviolence in all of life is the moral paradigm. I also believe that conscientious objection to war is morally correct. Was alternative service a legitimate response to objection to the war in Vietnam? Do only non-Mennonites, non-Anabaptists, non-Protestants, non-Christians, the ungodly fight wars? If aggressive land troops were invading the U.S., would I conscientiously object to that war? Is there a difference between a protective war and an aggressive war, or of one 12,000 miles from Colorado and one here? Is personal defense different from national defense? Is pacifism, as Catholic William Buckley strongly proclaims, a Christian heresy? I am afraid that I don't have any unqualified answers.

I have occasionally wondered, having the wisdom of hindsight, what I would do if I were once again back in the 1960's, faced with the same decisions and choices. I don't think that I would do the same thing. I say that because I feel that my statement of conscientious objection and peace witness were minimal. Because of the medical school setting with a large population of 22 to 26-year-olds, I am sure that many of my peers and co-workers were unaware that my job was fulfilling my alternative service requirement. Marlin, John, and I tried to blend in rather than stand out. We were indeed the "quiet in the land."

Once again, I am afraid that I don't have any unqualified answers as to what I would do differently. What would have been more appropriate? What would have been more effective? Where would a peace witness have been more effective? Since the war was in Southeast Asia, I believe that the major peace witness should have also been in Southeast Asia.

I believe that I would have had a more effective and fulfilling alternative service experience and peace witness by working directly to counter the destructiveness of war. Having gone through this experience, I feel that I can provide advice and perspective to persons, including our children, that may someday face a similar situation. And, even in the absence of a U.S. draft, I believe that we should encourage and support those who choose to go to the areas of conflict to be peacemakers."

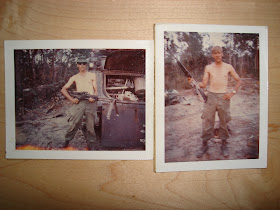

Clair Miller - Vietnam - Circa 1968

Doug

ReplyDeleteI suspect that the boy in the picture would not fit in those fatigues anymore.

I do not remember the comments you wrote on Vietnam, but I do remember the serious thought you and I had about going to Vietnam. Your choices were made with a lot of thought and committment and I'll always respect you for that. I still believe your choice to work at the hospital in Denver took as much courage as my choice to get drafted.

Thank you for the kind words and the funny looking pictures.

wool seeya - Clair

Clair - thanks for your kind words. As they say, we go back a long way and hopefully "wool seeya" soon somewhere down the road.

ReplyDeletedoug

I was drafted and served 14 months in Vietnam with an infantry batallion in the 9th Infantry Division during the bloodiest period of the war. (The war was actually a lot harder on my parents than it was on me.) Am thankful for the experience and getting home in one piece. I have no problem with pacifism or pacifists, but as I jokingly told cousin Doug, "as long as there aren't too many of you."

ReplyDelete